Education is a cornerstone for societal advancement and progress, and Uganda, nestled in East Africa, embodies this truth. Despite notable strides, Uganda’s education system confronts multifaceted challenges that impede its growth. This article delves into Uganda’s nuanced landscape of education, celebrating its achievements while shedding light on persistent obstacles.

Historical Trajectory

Colonial Legacy and Post-Independence Transition: Uganda’s education system bears the imprint of its colonial past. British influences shaped the foundation of the education system, with missionary schools catering to a select few. After post-independence, education emerged as a tool for nation-building and social transformation. The government’s introduction of Universal Primary Education (UPE) in 1997 marked a watershed moment, significantly boosting primary school enrollment rates. However, infrastructure inadequacies and resource disparities across regions persistently hamper access.

Access to Education

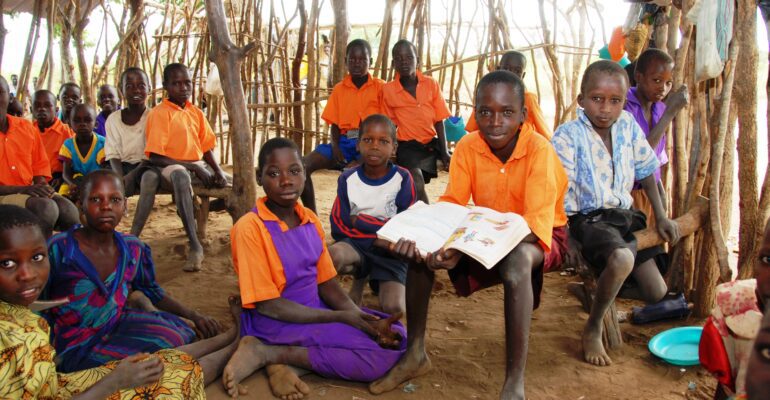

Bridging the Urban-Rural Divide: A core challenge lies in ensuring uniform access to education. While primary school enrollment has risen, rural-urban disparities persist. Remote areas have limited infrastructure, often lacking proper school facilities and qualified teachers (See Building Schools in Uganda.). Poverty, another significant barrier, can push children out of school and into labor. Furthermore, cultural norms and gender biases result in parents favoring boys over girls in education opportunities.

Gender Disparities

Empowerment Through Education: Uganda has made substantial strides in promoting gender equality in education to break entrenched stereotypes. Girls’ enrollment rates have improved, but the challenge of retaining them in school remains due to factors such as early marriages and teenage pregnancies. International Non-Governmental Organizations (“INGOs”), like The Teach Them To Fish Foundation, work tirelessly to dismantle these barriers and uplift the status of Ugandan women through education.

Quality of Education

Current Structure: Uganda has organized its educational structure consisting of primary, lower secondary, upper secondary, advanced secondary, and post-secondary schools.

Primary education in Uganda consists of seven grades, known as Primary One (P1) through Primary Seven (P7). Primary school lasts seven years and is generally for children between 6 and 13 years old. The curriculum includes a range of subjects such as Mathematics, English, Science, Social Studies, and local languages (depending on the region). Religious and physical education are also standard components of the curriculum. As students progress through their grades, the curriculum becomes more advanced and specialized in each subject. Teachers assess primary school students through regular tests and examinations. At the end of P7, students must take a Primary Leaving Examination (PLE), a national standardized exam. Uganda uses the PLE results to determine whether students’ progress to secondary education, an essential milestone in their educational journey. Teaching methods in Ugandan primary schools can vary, but they often involve a combination of lectures, group activities, discussions, and hands-on learning experiences. The approach might vary based on the school’s resources and the teaching philosophy of the educators. Students commonly wear uniforms in primary schools when their parents can afford them, which is often rare in rural areas. They consist of a specific color and style determined by the school. Schools in Uganda generally have rules and guidelines for behavior and discipline to create a conducive learning environment.

After completing P7 and passing the PLE, students proceed to lower secondary school, often called “O-Level” (Ordinary Level). This cycle typically covers four years, from Senior One (S1) to Senior Four (S4). During this time, students study a range of subjects, including core subjects like Mathematics, English, Sciences, and Social Studies, as well as elective subjects based on their interests and career aspirations.

After completing lower secondary education and passing the Uganda Certificate of Education (UCE) exams at the end of S4, students who wish to continue their education move on to upper secondary school, often referred to as “A-Level” (Advanced Level). This cycle lasts two years, from Senior Five (S5) to Senior Six (S6). Students usually specialize in specific subjects during this stage, focusing on those relevant to their intended career paths or further education. At the end of S6, students take the Uganda Advanced Certificate of Education (UACE) exams. The UACE results are crucial for students seeking admission to higher education institutions, such as universities, colleges, or vocational training institutes.

After completing secondary education, students in Uganda have several options. Those who perform well on their UACE exams can apply to universities or other higher education institutions, such as a polytechnical institute, to pursue bachelor’s degree programs in various fields or certificate programs in specific areas of study. Students interested in practical skills and technical careers can enroll in vocational institutes for specialized agriculture, carpentry, mechanics, and more training. While not as common as pursuing further education, some students at this level may enter the workforce directly after completing secondary education if they have acquired skills that make them employable.

A Holistic Approach: Quality education hinges on factors like teacher training, curriculum relevance, and modern teaching methods. Many Ugandan teachers lack formal training and face daunting class sizes, hindering personalized instruction. Outdated pedagogical practices and limited access to learning resources further compromise learning outcomes. Initiatives focusing on teacher development and curriculum reform are pivotal in enhancing educational quality.

Higher Education: Navigating Challenges: Uganda’s higher education sector faces its own set of challenges. Funding limitations impede infrastructure development, and outdated facilities hinder effective teaching and research. At the same time, institutions like Makerere University enjoy international recognition, but the sector grapples with issues such as brain drain as talented Ugandans seek better opportunities abroad.

Government Initiatives and International Collaborations: In partnership with INGOs like The Teach Them To Fish Foundation and donor agencies, the Ugandan government has launched various initiatives to revitalize the education system. The Uganda National Minimum Education Standards framework sets guidelines for quality across schools, and UPE aims to ensure universal primary education. Organizations like UNICEF provide technical support and resources to complement national and INGO efforts.

Charting a Path Forward: A Collective Responsibility: Education in Uganda is at a pivotal juncture, demanding strategic interventions. The road ahead involves collaborative endeavors among government, local communities, and INGO partners. Investing in teacher capacity, modernizing teaching methods, and fostering inclusivity can fortify the education system against future challenges.

Comments are closed.